As I promised, in this second part of the analysis of the book called “The China Study” I will explain if the dairy producs are carcinogenic or not.

Friendly consideration: because the idea that milk is a carcinogenic has become as popular as the idea that we have to eat the fruit between meals so as not to ferment the bacteria that are non-existent in the stomach, it will be a loooooooooooooooooooong and scientifically detailed article.

If you just want to have fun reading a personal opinion about dairy products and cancer, close this article, it’s not for you.

For those who want to understand why we recommend cancer patients to continue to consume milk, fermented dairy and cheese during both treatment and the relapse prevention period, I will begin by answering in detail one of the written comments in response to first part.

And I think it’s important to do this because I think this commentary mirrors the ideas transmitted in a popular way from one patient to another and from benevolent people to the oncological patient:

– “Things are never simple. Let’s ask ourselves: Why did not Asian people consume dairy for 6,000 years? Dairy is known to be acid products. And in the Asian diet abounds vegetables”.

Ignoring the fact that the author of the comment does not know that blood alkalinisation is as dangerous to health as acidification, what I do not understand is how you can write a valid comment like “things are never easy” in the same phrase that you write that “Asian people dit not consume dairy for 6,000 years“.

– Which Asians have not consumed dairy for 6,000 years?

The fact that some believe the Asians do not consume dairy ignores how geographically Asia is, it is just a guess based on the popular image promoted by green grass fans on the other side of the fence – a kind of Utopian China where live mythical antioxidant survivors.

Here are two Chinese milk advertisements of the 1930s and 1933s respectively, the first describing the mother who feeds her healthy baby with milk, and the second – an elderly woman who says she is healthy because she drinks a glass of milk daily in the morning and in the evening.

– So, did Asians not consumed dairy for 6,000 years, and then the marketers decide to start to advertise in 1930 to introduce a new product to the Chinese market?

In the database used by researchers quoted by Campbell himself, the inhabitants of one of the 65 regions studied – Tuoli – consumed on average 865.5 g dairy/day, but not because milk ads were so effective as to persuade even the Asians who did not consume dairy 6,000 years ago to consume them, but simply because the Tuoli region looks like this:

According to this database, the inhabitants of Tuoli:

1) had an average daily consumption of:

- 865.5 g dairy products

- 371.6 g wheat flour products

- 121 g of meat.

2) consumed extremely rarely or not at all:

- Potatoes – 5-6 times a year

- Vegetables – twice a year

- Fruits – maximum once a year

- Legumes – never

- Nuts – never

- Eggs – never

- Fish – never

- Vegetable oil – never

So these Asians lived with dairy, bread and meat, most of them being shepherds.

Considering that milk has an average content of 80% casein and an average protein content of about 4 g/l, we can calculate that casein intake in the Tuoli region was 27.39 g/day.

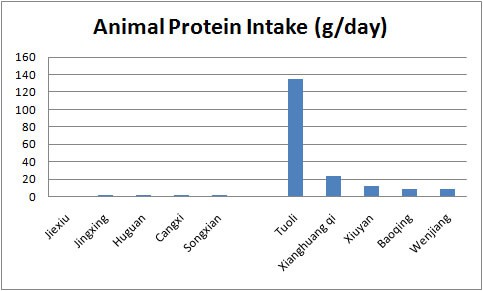

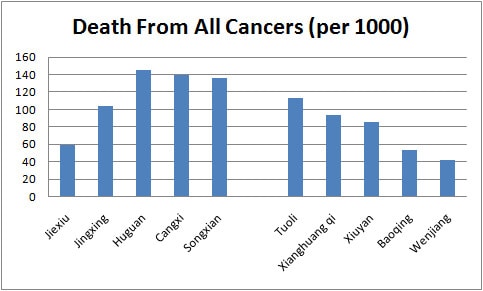

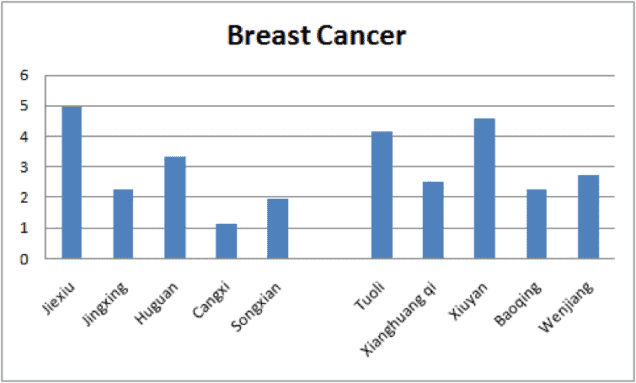

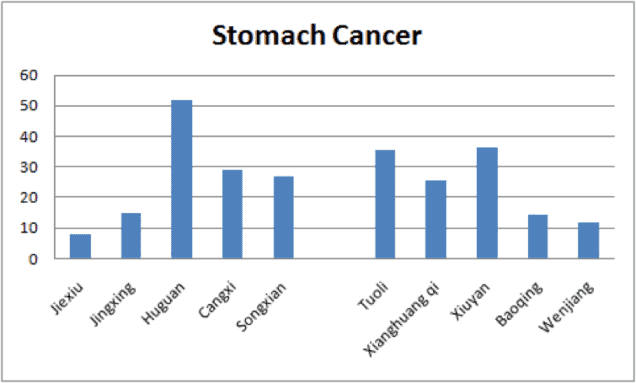

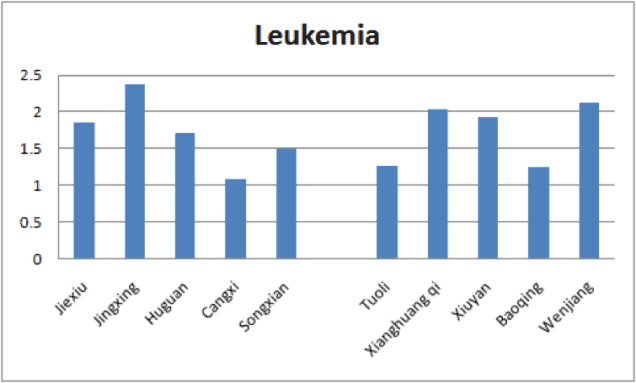

ANow let’s compare the risk of mortality through cancer due to a daily intake of 27.39 g of casein and one of 0 g by comparing them to:

– vegans from Jiexiu, Jingsing, Huguan, Cangxi, or Songxian regions = average intake of 0 g casein/day

with

– omnivores from the Tuoli region = average intake of 27.39 g casein/day.

And I invite you to do this as a parallel to Campbell’s famous study in which mice fed 20% of casein –they say – have cancer.

And I write “they say” because you can read even in that study că that none of the mice actually did cancer, but only precancerous lesions, of which 95% were self-healing, the researchers assuming that the remaining 5 % will turn into cancer at some point.

Here are some graphs based on the data obtained by researchers who analyzed the food intake of the people in the 65 regions of China with a vegan or omnivorous diet:

Nevertheless, according to Campbell:

“People who ate the most animal-based foods got the most chronic disease. Even relatively small intakes of animal-based food were associated with adverse effects. People who ate the most plant-based foods were the healthiest”.

Simplier, Campbell argues that “people with the highest consumption of animal food were the most unhealthy, and those who fed plants were the healthiest“.

Now, look at the graphs above and judge with your own brain the validity of this statement.

This is just one of many examples of what Campbell’s quoted studies say and what Campbell says that these studies say.

So – leaving aside more or less famous personal opinions – let’s answer the following 3 questions based on the current scientific literature:

- Are carcinogenic milk proteins?

- Does milk or dairy daily consumption increase the risk of mortality in cancer patients?

- Does milk or dairy daily consumption increase the risk of cancer in healthy people?

1) Are carcinogenic milk proteins?

Campbell’s famous statement that we can activate / inactivate “cancer” by simply lowering casein intake is another example of the difference between what the studies quoted by him say and what he says say these studies say:

“casein proved to be so powerful in its effect that we could turn on and turn off cancer growth simply by changing the level consumed”

It would be absolutely brilliant to treat cancer so easily!

Just as I wrote in the first part of this series of articles, the studies quoted or made by Campbell did not „prove“ the carcinogenicity of casein in any way, but rather that increased intake of casein increases the survival of mice exposed to a substance carcinogens such as aflatoxin.

Studies show that the casein intake:

- prolongs survival – Engel and Copeland, 1952

- has antimutagenic effect – Van Boekel et al., 1993

- has anticancerogenic activity both in vitro and in vivo – Goeptar et al., 1997

- stimulates the immune system – Parodi, 1998

- stimulates the apoptosis of intestinal malignant cells – Perego et al., 2012

And other milk proteins:

- provide anticarcinogenic protection in case of exposure to carcinogens – McIntosh et al., 1995

- stimulate the immune system – Meisel and FitzGerald, 2003

- inhibit the growth of malignant cells – Meisel, 2004

- have antimutagenic effect – Parodi, 2007

- inhibit angiogenesis – Tung et al., 2013

- support the efficacy of treatment and the healing of the patient with cancer – Chen et al., 2014

- improve prognosis of patients with advanced cancer (stage III, IV) – Engelen et al., 2015

2) Daily milk or dairy consumption increases the risk of mortality in cancer patients?

- Consumption of yoghurt and buttermilk can provide protection against breast cancer – van’t Veer et al., 1989

- Consumption of 6 servings of dairy products per day is not detrimental to patients with rectal cancer – Karagas et al., 1998

- Consumption of fermented dairy contributes to the preservation of intestinal integrity during radiotherapy – Salminen et al., 1998

- Milk consumption during paclitaxel chemotherapy increases the effectiveness of treatment and decreases the incidence of side effects – Sun et al., 2011

- Consumption of skimmed milk and dairy products does not increase the risk of mortality in patients with prostate cancer diagnosis – Petterson et al., 2012

- Milk consumption lowers the risk of mortality in colon cancer patients – Yang et al., 2014

- Consumption of milk and dairy products lowers the risk of mortality by cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer – Elwood et al., 2008

- And, in general, it helps to counteract side effects of oncological treatment:

- anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effect – Mukhopadhya and Sweeney, 2016

- antihypertensive effect – Pepe et al., 2013

- supports type II diabetes prevention and sarcopenic obesity – McGregor and Poppitt, 2013

- associates a lower level of uric acid – Choi, Liu and Curhan, 2005

- improves hepatic transaminase levels and contributes to the reduction of total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol – Nabavi et al., 2014

3) Daily milk or dairy consumption increases the risk of cancer in healthy people?

- Moderate intake of milk and dairy products does not increase the risk of cancer – Davoodi, Esmaeili and Mortazavian, 2013

- Men who consume milk frequently have a 60% lower risk of colon cancer than those who do not consume milk – Jing Ma et al., 2001

- A low consumption of fermented dairy is associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer – De Mesquita et al., 1991

- Consumption over two portions of dairy is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer ER + in menopausal women – McCullough et al., 2005

- Increased intake of buttermilk and yogurt may lower the risk of bladder cancer – Larsson et al., 2008

- Consumption of fermented dairy products lowers the risk of liver cancer – Rayes, El-Naggar and Mehanna, 2008

- Consumption of milk and dairy products lowers the risk of colorectal cancer – Aune et al., 2012

- Consumption of milk and dairy products does not increase the risk of lung cancer – Yu et al., 2016

- Consumption of milk and dairy products is associated with a decrease in the risk of colon cancer, bladder cancer, gastric cancer and breast cancer – Thorning et al., 2016

- The meta-analysis of 22 cohort studies that analyzed 1,566,940 people and 5 case studies that analyzed 33,372 Asian people over a 10-year period demonstrates that a minimum intake of over 400 ml of yogurt or dairy products per day is associated with a low risk of breast cancer – Zang et al., 2015

- The meta-analysis of 10 population studies analyzing the eating habits of 534,536 people claims that daily intake of at least 250 ml of milk reduces the risk of colorectal cancer – Cho et al., 2004

- The meta-analysis of 52 studies analyzing milk intake from the perspective of fat, growth hormones, IGF-1 and estrogen contaaining does not support the association between dairy consumption and breast cancer risk – Parodi, 2013

- The meta-analysis of 45 studies that analyzes 26,769 cases does not support the epidemiological assumption that dairy intake would increase the risk of prostate cancer – Huncharek, Muscat, Kupelnick, 2008

- The meta-analysis of 17 case studies and 6 population studies analyzing a total of 3,256 cases suggests that milk intake does not increase the risk of gastric cancer, dairy consumption lowering this risk – Guo et al., 2015

- The meta-analysis of 19 studies examining the consumption of skimmed milk, whole milk, yoghurt and lactose does not support any association between the intake of these foods or lactose in particular and the risk of ovarian cancer – Liu et al., 2015

- The meta-analysis of 32 studies of milk, yogurt, dairy and cheese consumption claims that the intake of these foods is not associated with an increased risk of lung cancer – Yang et al., 2016

Here are dozens of studies that claim that dairy products are not carcinogenic for healthy people and that milk and dairy intake decreases the risk of mortality and supports the effectiveness of oncology treatment.

If you are diagnosed with cancer and you are tempted to remove milk and meat from food, packed with various pseudo-treatments such as veganism, detox, bicarbonate, red beet juice, wonder mushrooms, and vitamin supplements C or other antioxidants instead of or with oncology, please think:

– How powerful should these malignant cells be that only 1, 2 or 5 cm from you endanger the survival of your entire body?

The malignant cell is the queen of survival, a real chameleon relaxed in front of such simplistic strategies, strategies that it will use to survive, evolve and multiply precisely because you deliver it on a platter:

- has the ability to use antioxidants to inactivate free radicals that could prevent it from multiplying and damaging it by generating apoptosis – Seifried et al., 2003

- has the ability to survive and develop without glucose when conditions become unfavorable – Alfarouk et al., 2011

- is a black glucose hole – Kroemer and Pouyssegur, 2008;

- co-administration of antioxidant supplements reduces side effects, but decreases the effectiveness of radiotherapy – Bairati et al., 2005

- co-administration of antioxidant supplements decreases the effectiveness of chemotherapy and radiotherapy – Lawenda et al., 2008

I will write a more detailed article on the harmfulness of antioxidant supplementation during oncology treatment because the use of such pseudo-oncological products can even transform the cancers that are initially treatable into incurable cancers.

What I want to emphasize now is that by oncological nutrition we can only support the efficiency of allopathic treatment, not cure a disease like cancer!

Anyone who claims otherwise has no idea what he’s saying – on the money, the health and, unfortunately, sometimes even on the life of the oncological patient.

Utopical China painted in pink by Campbell sells cancer patients, through pseudo-oncological industry traders, high hopes elevates to a universal panacea.

„…that it is better to tell the cancer patient to eliminate milk and meat, drink red beet juice and take antioxidant supplements than leave it so confused without trying to help it with an advice!“

Quoted studies

- Alfarouk, Khalid O., et al. “Evolution of tumor metabolism might reflect carcinogenesis as a reverse evolution process (dismantling of multicellularity).” Cancers 3.3 (2011): 3002-3017.

- Aune, D., et al. “Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.” Annals of oncology 23.1 (2012): 37-45.

- Bairati, Isabelle, et al. “Randomized trial of antioxidant vitamins to prevent acute adverse effects of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer patients.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 23.24 (2005): 5805-5813.

- YF Chen, H., et al. “Potential clinical applications of multi-functional milk proteins and peptides in cancer management.” Current medicinal chemistry 21.21 (2014): 2424-2437.

- Chen, Wanqing, et al. “Cancer statistics in China, 2015.” CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 66.2 (2016): 115-132.

- Cho, Eunyoung, et al. “Dairy foods, calcium, and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96.13 (2004): 1015-1022.

- Choi, Hyon K., Simin Liu, and Gary Curhan. “Intake of purine‐rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.” Arthritis & Rheumatism 52.1 (2005): 283-289.

- Davoodi, H., S. Esmaeili, and A. M. Mortazavian. “Effects of milk and milk products consumption on cancer: a review.” Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 12.3 (2013): 249-264.

- De Mesquita, H. Bueno, et al. “Intake of foods and nutrients and cancer of the exocrine pancreas: A population‐based case‐control study in the Netherlands.” International journal of cancer 48.4 (1991): 540-549.

- Elwood, Peter C., et al. “The survival advantage of milk and dairy consumption: an overview of evidence from cohort studies of vascular diseases, diabetes and cancer.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition 27.6 (2008): 723S-734S.

- Engel, R. W., and D. H. Copeland. “The influence of dietary casein level on tumor induction with 2-acetylaminofluorene.” Cancer research 12.12 (1952): 905-908.

- Engelen, M. P. K. J., et al. “High anabolic potential of essential amino acid mixtures in advanced non-small cell lung cancer.” Annals of Oncology (2015): mdv271.

- Goeptar, Arnold R., et al. “Impact of digestion on the antimutagenic activity of the milk protein casein.” Nutrition Research 17.8 (1997): 1363-1379.

- Guo, Yanjun, et al. “Dairy consumption and gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies.” Nutrition and cancer 67.4 (2015): 555-568.

- Huncharek, Michael, Joshua Muscat, and Bruce Kupelnick. “Dairy products, dietary calcium and vitamin D intake as risk factors for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of 26,769 cases from 45 observational studies.” Nutrition and cancer60.4 (2008): 421-441.

- Karagas, Margaret R., et al. “Effects of milk and milk products on rectal mucosal cell proliferation in humans.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 7.9 (1998): 757-766.

- Kroemer, Guido, and Jacques Pouyssegur. “Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel.” Cancer cell 13.6 (2008): 472-482.

- Larsson, Susanna C., et al. “Cultured milk, yogurt, and dairy intake in relation to bladder cancer risk in a prospective study of Swedish women and men.” The American journal of clinical nutrition 88.4 (2008): 1083-1087.

- Lawenda, Brian D., et al. “Should supplemental antioxidant administration be avoided during chemotherapy and radiation therapy?.” Journal of the national cancer institute 100.11 (2008): 773-783.

- Liu, Jing, et al. “Milk, yogurt, and lactose intake and ovarian cancer risk: A meta-analysis.” Nutrition and cancer 67.1 (2015): 68-72.

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) . Toxicological evaluation of certain veterinary drug residues in food: Estradiol-17β progesterone and testosterone. WHO Food Additives Series.2000b;43

- Ma, Jing, et al. “Milk intake, circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor-I, and risk of colorectal cancer in men.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 93.17 (2001): 1330-1336.

- McCullough, Marjorie L., et al. “Dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 14.12 (2005): 2898-2904.

- McGregor, Robin A., and Sally D. Poppitt. “Milk protein for improved metabolic health: a review of the evidence.” Nutrition & metabolism 10.1 (2013): 1.

- McIntosh, Graeme H., et al. “Dairy proteins protect against dimethylhydrazine-induced intestinal cancers in rats.” Journal of Nutrition 125.4 (1995): 809-816.

- Meisel, H., & FitzGerald, R. J. (2003). Biofunctional peptides from milk proteins: mineral binding and cytomodulatory effects. Current pharmaceutical design, 9(16), 1289-1296.

- Meisel, Hans. “Multifunctional peptides encrypted in milk proteins.” Biofactors 21.1-4 (2004): 55-61.

- Mukhopadhya, Anindya, and Torres Sweeney. “Milk Proteins: Processing of Bioactive Fractions and Effects on Gut Health.” MILK PROTEINS (2016): 83.

- Nabavi, S., et al. “Effects of probiotic yogurt consumption on metabolic factors in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.” Journal of dairy science 97.12 (2014): 7386-7393.

- Parodi, Peter W. “A role for milk proteins in cancer prevention.” Australian journal of dairy technology 53.1 (1998): 37.

- Parodi, P. W. “A role for milk proteins and their peptides in cancer prevention.” Current pharmaceutical design 13.8 (2007): 813-828.

- Parodi, Peter W. “Impact of cows’ milk estrogen on cancer risk.” International dairy journal 22.1 (2012): 3-14.

- Parodi, Peter W. “Dairy product consumption and the risk of breast cancer.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition 24.sup6 (2005): 556S-568S.

- Pepe, Giacomo, et al. “Potential anticarcinogenic peptides from bovine milk.” Journal of amino acids 2013 (2013).

- Perego, Silvia, et al. “Casein phosphopeptides modulate proliferation and apoptosis in HT-29 cell line through their interaction with voltage-operated L-type calcium channels.” The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 23.7 (2012): 808-816.

- Pettersson, Andreas, et al. “Milk and dairy consumption among men with prostate cancer and risk of metastases and prostate cancer death.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 21.3 (2012): 428-436.

- Rayes, Amna AH, Sabah MM El-Naggar, and Nayra Sh Mehanna. “The effect of natural fermented milk in the protection of liver from cancer.” Nutrition & Food Science 38.6 (2008): 578-592.

- Salminen, E., et al. “Preservation of intestinal integrity during radiotherapy using live Lactobacillus acidophilus cultures.” Clinical radiology 39.4 (1988): 435-437.

- Seifried, Harold E., et al. “The antioxidant conundrum in cancer.” Cancer Research 63.15 (2003): 4295-4298.

- Sun, Xueying, et al. “Dairy milk fat augments paclitaxel therapy to suppress tumour metastasis in mice, and protects against the side-effects of chemotherapy.” Clinical & experimental metastasis 28.7 (2011): 675-688.

- Thorning, Tanja Kongerslev, et al. “Milk and dairy products: good or bad for human health? An assessment of the totality of scientific evidence.” Food & Nutrition Research 60 (2016).

- Tung, Yu-Tang, et al. “Bovine lactoferrin inhibits lung cancer growth through suppression of both inflammation and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor.” Journal of dairy science 96.4 (2013): 2095-2106.

- van’t Veer, Pieter, et al. “Consumption of fermented milk products and breast cancer: a case-control study in The Netherlands.” Cancer research 49.14 (1989): 4020-4023.

- Yang, Baiyu, et al. “Calcium, vitamin D, dairy products, and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors: the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.” Journal of Clinical Oncology (2014): JCO-2014.

- Yang, Yang, et al. “Dairy Product, Calcium Intake and Lung Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis.” Scientific reports 6 (2016).

- Yu, Yi, et al. “Dairy consumption and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.” OncoTargets and therapy 9 (2016): 111.

- Zang, Jiajie, et al. “The Association between Dairy Intake and Breast Cancer in Western and Asian Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of breast cancer 18.4 (2015): 313-322.

- Zeitoun, M. M., I. S. Salem, and S. M. Ahmed. “Evaluation of the Male and Female Sex Steroid Hormones Residues in Eggs, Milk and their Productsin Alqassim Region.” Journal of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences 8.1 (2015).

P.S. Are laptele impact estrogenic?

Unele dintre pacientele cu cancer mamar cu care lucrez nu consumă lapte de teama impactului estrogenic.

– Conţine laptele estrogen?

– Evident da, chiar 17β-estradiol – cel mai activ tip de estrogen.

Doza maximă admisă de OMS (Organizaţia Mondială a Sănătăţii) este de 5 μg 17β-estradiol/kg corp.

De exemplu, o femeie de 60 kg poate avea un aport alimentar maxim 60 x 5 μg = 300 μg 17β-estradiol pe zi.

1 l lapte contine 0,1571 μg17β-estradiol – Zeitoun si colab., 2015

Dar 95% din estradiolul ingerat este inactivat gastro-intestinal – Parodi, 2012

Această inactivare gastro-intestinală a estradiolului ingerat face ca, din cele 0,1571 μg aduse de 1 l lapte, doar 0,007855 μg să ramână active.

Deci, cantitatea de lapte pe care ar trebui să o consume într-o zi o femeie de 60 kg pentru a genera impact estrogenic este de 38.192 litri.